During the past few years those of us searching for Irish ancestors have been blessed with some major new collections. These include the digitization and indexing of Roman Catholic church records – now available for free at FindMyPast.ie. Church records, such as baptisms, marriages and burials, are critical tools for identifying individuals and relationships prior to the start of civil registration in Ireland. A significant majority of the population attended the Catholic church, when allowed, so the importance of free access to these records can’t be overstated. This is especially true prior to 1880.

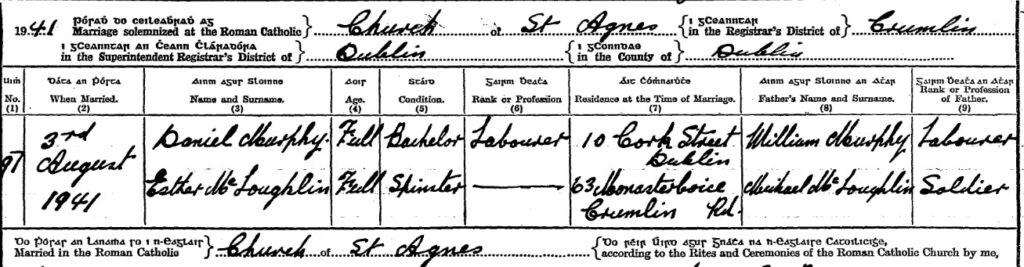

After 1864, the recording of births, marriages and deaths was mandated and civil registrations became increasingly important.

These documents in the Republic of Ireland are now indexed and online at www.irishgenealogy.ie – also for free. As John Grenham, the dean of Irish genealogical research, has observed:

there is no doubt that making the record images free online is the single biggest advance in Irish record access since the destruction of the PRO [Public Records Office] in 1921.1

So, after the recent completion of those two monumental efforts, what has the past year given us? Actually, quite a bit. And in 2020, the big progress has been at two sites – RootsIreland and Ancestry.

RootsIreland

RootsIreland.ie is the umbrella website for the dozens of county genealogical societies which make up the Irish Family History Foundation (IFHF). These organizations have been transcribing baptisms, marriages and burials from multiple denominations as well as from Ireland’s civil registrations. This work is not yet complete, but they do have an enormous number of those records transcribed and indexed. It is a great complement to the digitized Roman Catholic records at FindMyPast.ie and the civil registrations at www.irishgenealogy.ie.

In the past year they have added almost 600,000 records to their collection. These added records are from over a dozen of Ireland’s 32 counties. The major additons were:

| County | Records | Description |

| Tipperary | 20,000 | Roman Catholic (RC) baptisms |

| Clare | 61,000 | RC & Civil Records |

| Kilkenny | 41,500 | Assorted parish records |

| Limerick | 11,000 | Assorted parish records |

| Sligo | 22,000 | Assorted parish records |

| Kerry | 220,000 | RC baptisms & marriages |

| Cork | 61,500 | RC parish records |

| Mayo | 79,540 | Baptism/Marriage/Burials – all faiths |

| Wicklow | 34,000 | Burials – mostly COI, some RC |

| Armagh | 41,000 | Parish records & gravestones – all faiths |

| Westmeath | 13,000 | COI parish records & gravestones |

Ancestry

In March of this year Ancestry.com added three large collections of Irish records that are extremely valuable for genealogists. These collections provide information on ordinary citizens who are rarely identified in most official records. All three are also geographically dispersed across all of Ireland.

| Collection | Records |

| Ireland, Prison Registers, 1790-1924 | 3.1M |

| Petty Court Sessions, 1818-1919 | 23.2 M |

| Dog License Registrations, 1810-1926 | 7.4 M |

Prison Registers

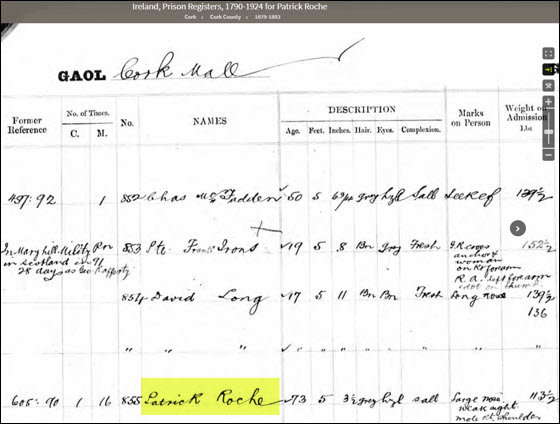

The Prison Registers provide plenty of information on people like Patrick Roche from Skibbereen in County Cork. Patrick was arrested for three offenses and sentenced to 7 days in jail (“gaol”) for each. We can see from this record in 1892 that he was 73 years old at the time of his incarceration.

We also learn that Patrick was 63 inches tall, weighed 113½ pounds, had grey hair, hazel eyes, a large nose, a sallow complexion, “weak sight” and a large mole on his right shoulder. Patrick’s religion was noted as Roman Catholic and he resided in Skibbereen, County Cork, working as a “fish dealer.” His offense was that he “allowed his mule to wander abroad.” According to the Justice of the Peace in Skibbereen. Patrick’s offenses occurred on April 17th & May 25th and his sentence was projected to end on June 15th of 1892. Quite a bit of information if Patrick is your ancestor!

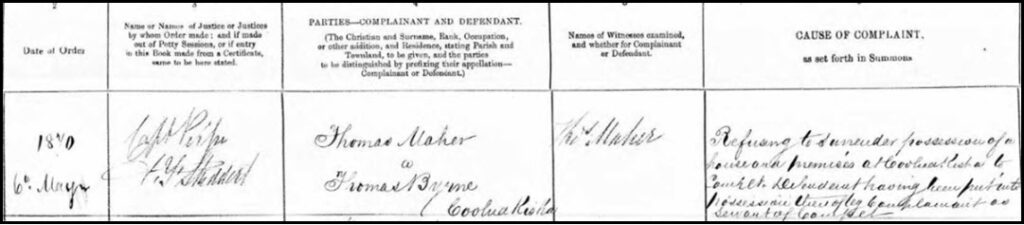

Petty Court Sessions

Those Prison Registers contain 3.1 million records and cover the entire country. That’s a wide net and it captures a lot of average citizens like Patrick. However, The Irish Petty Court Sessions contain over 23 million records documenting relatively small crimes, misconduct, fights between neighbors and domestic disputes. Again, these records provide information on many otherwise poorly documented people.

In this case the complainant, Thomas Maher, has taken Thomas Byrne to court over possession of a house and property. The amount of personal information is less than that found in the prison records but, given the size of this database, we are much more likely to find our ancestors.

Dog Licenses

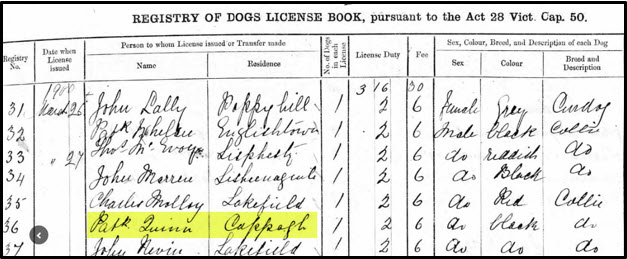

In a place and time when almost everyone farmed, dogs were valued and almost ubiquitous. Therefore, another collection with broad coverage, especially in the countryside, is Dog License Registrations. This bureaucratic requirement ensnared almost everyone regardless of wealth, politics or religion. Our example is from County Galway and documents Patrick Quinn of Rahoon Parish.

Patrick applies for a license for his black collie, a male, on March 27, 1900. We also learn what could be an important fact – that Patrick lives in the “townland” of Cappagh, within his parish of Rahoon. Ireland is famous for having throngs of people with the same names. A specific townland, basically a neighborhood, could be a critical clue for determining the identity of your “Patrick Quinn.”

These collections at RootsIreland and Ancestry are great additions to the growing body of online resources for those of Irish descent. Unfortunately, they require a subscription to these two databases. But, when combined with the Roman Catholice church records at FindMyPast, the civil registrations at www.irishgenealogy.ie and Griffith’s valuation at www.askaboutireland.ie, all of which are free, they make for a very powerful set of tools.

Let’s hope that 2021 provides us as much!

1 John Grenham, Tracing Your Irish Ancestors, 5th Edition (Dublin: Gill Books, 2019), 6.